-- What were some of the challenges you encountered during development?

Collecting the cross-sectional images of tuna tails was a challenge. We needed to have a huge amount of sample data to have the AI system learn what takes artisans 20 or 30 years of training to do, but the seafood markets where they inspect tuna day in and day out are not places where outsiders can easily gain access. So we had to shift our approach and think about who would have large amounts of data on tuna. Then we found Sojitz, a general trading company that operates a global tuna business.

We created a prototype of the application using data on tuna that we had collected at Misaki Port, which we then took to Sojitz. We gave them an overview of the project and learned that Sojitz was also encountering their own issues with tuna inspections, such as differences in the accuracy of individual artisans and their tuna purchases being hit or miss. TUNA SCOPE is able to offer a stable supply of high-quality tuna that meets a certain standard, regardless of who does the inspection. Their thinking and our thinking were in alignment, and they joined the project.

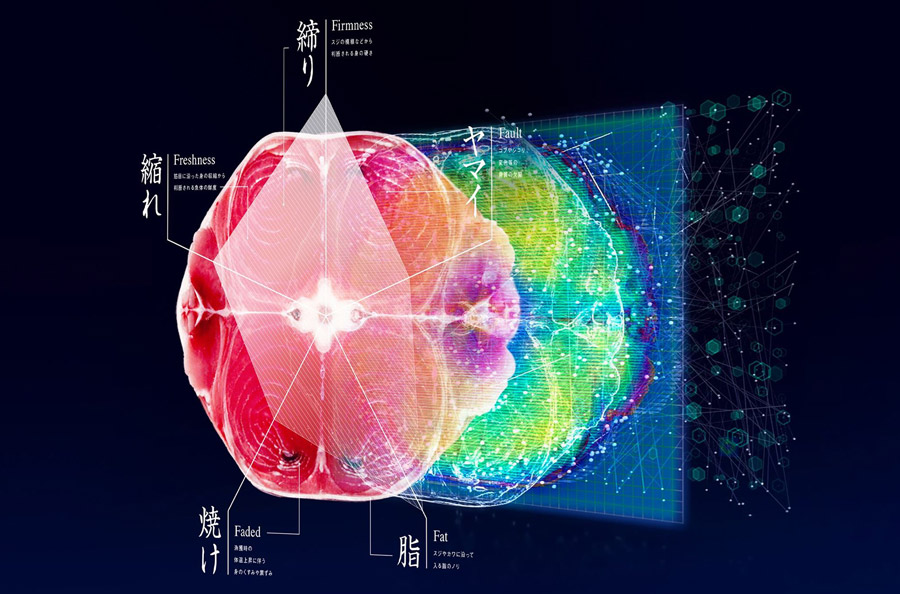

Now that we had the cooperation of Sojitz, we were able to collect 4,000 images of sample data on yellowfin tuna. We used a smartphone to photograph the cross section of these samples and compared them with the results of artisan inspections. We then fed these data as a set into the AI system, and in just one month, the system succeeded in learning a volume of data equivalent to what an artisan learns in 10 or more years of training, looking at one tuna a day.

When we deployed the AI system we developed on a smartphone and tested it, we found that it was able to achieve a high rate of accuracy, matching the inspection results of an artisan with a 35-year career approximately 85% of the time. In our most recent tests, the AI system was able to correctly judge, with more than 90% accuracy, tuna that had been graded by a skilled artisan as high quality.

-- You’ve also sold tuna that TUNA SCOPE has graded as the highest quality as “AI Tuna,” and conducted an on-the-spot survey.

In March 2019, Kantaro, a conveyor belt sushi restaurant at Tokyo Station that serves seafood bought directly from producers, added tuna that TUNA SCOPE had graded as highest quality to their regular menu as “AI Tuna” (280 yen, not including tax). It turns out that the restaurant sold approximately 1,000 plates of AI Tuna in five days, and the results of our survey showed that around 90% of customers felt that the tuna tasted better than other tuna in the same price range. Some of the comments from customers that left an impression on me were that the tuna actually tasted better than usual, and that the AI tool meant the customer could rest assured eat tuna that would be as delicious as they expected it to be.